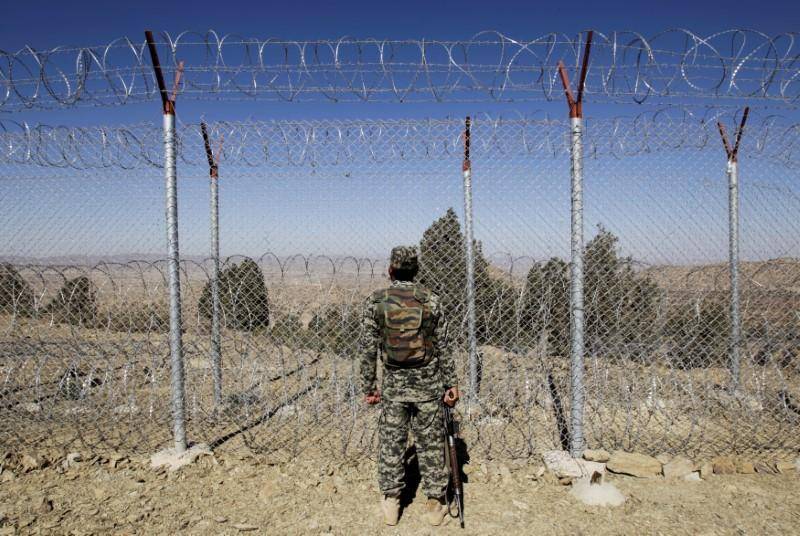

Pak Afghan border fencing, 443 Forts, 1,100 border posts on world's most difficult terrain

Shares

PESHAWAR: Pakistan’s military is pressing ahead with its plan to completely fence the 150-kilometre-long portion of the Pak-Afghan border billed as one of the most porous and perilous border regions in the world, according to a security official.

Thousands of soldiers and hundreds of vehicles are deployed at 14 different sites on a daily basis to undertake the arduous task of fencing the Pak-Afghan border — from Chitral to South Waziristan — putting in 7,000 man-hours for the installation of fabricated material.

The first phase of the project is likely to be completed by the end of 2018, which will see the fencing of 432km at the most critical points along the border.

The second phase, called “desirable”, would see the fencing of another stretch of 400km, the official said. The entire project, costing Rs10 billion, was set to be completed in the next two years.

The fence runs along some of the most inhospitable border regions, from snow-capped mountains to rugged terrains to lush green valleys. “It is going ahead day and night,” the official said.

“The Pak-Afghan border fencing is now a reality. We have broken the myth that this border is so perilous that it cannot be fenced. This is a project of strategic significance,” the security official said.

The fortification of the border would be augmented by border posts and an intrusion detection system, the official said. As part of the project, 150 of the total 443 forts had already been constructed, some built on mountaintops as high as 12,000 feet, while 1,100 border posts had also been established.

“This will serve as a strong line of defence,” the official said.

The huge undertaking has not come without human cost. Security officials say that in two months alone — July and August — an officer and a Junior Commissioned Officer embraced martyrdom on account of sniping from across the border. Three soldiers sustained injuries.

“It is tough,” a civilian construction worker who worked at the project in Mohmand tribal region said.

Wearing a helmet and bullet-proof vests, he said they would work in shifts and round the clock to complete the job. “Invariably, we would draw fire from across the border,” Dawar, who goes by one name.

But officials say the project is worth the human and material costs involved. “...The fallout of the war in Afghanistan in the last few decades negatively impacted us in terms of security and militancy,” the official said.