ISLAMABAD – Rearrangements of new realities after the withdrawal of theSoviet Union from Afghanistan in 1979, and the readjustment of post WWIIInternational Order into a multi-polar regionalized and globalized world,has led to the twosome power game in South Asia to continue via proxy. Inall, from the legacy of 9/11 to the unsubstantiated accusations of‘terrorist proxies,’ having safe havens for the *Haqqani* and the*Taliban,* Pakistanremains in a tender predicament despite being the ‘most allied non-NATOally’ of the US. The role of a frontline state for the US was playedunfailingly by Pakistan both during and after the-Cold War by joininganti-communist alliances like CENTO and SEATO and in the War on Terror(WoT) respectively. Pakistan was also a strategic ally to the CIA andfacilitated its biggest covert operation against Soviet forces inAfghanistan. It helped the US provide billions of dollars in weapons to theAfghan *Mujahideen*. Till then, India was on the opposite side of the fenceas it pursued a pro-Soviet policy.

Amidst the rise of a multi-polar politico-economy in a more regionalizedand globalized world, India has successfully attracted its economic anddiplomatic successes into new international opportunities. As such,shifting its romance towards the US after the Soviet Union was morelucrative to its politico-strategic clash with Pakistan.

In fact, India was already a better choice for the US. It had itscomprehensive industrial base with 10% economic growth rate in early1990’s, at the time of the breakup of the Soviet Union. The policy ofself-reliance pursued uninterruptedly by India ever since its independencealso adhered well in an increasingly more integrated internationalfinancial system despite new political dynamics. Its geo-strategic locationnext to the emerging US new competitor, China, embodied bettertransactional value. The $400 billion Foreign Exchange Reserves, 7.4percent economic growth rate almost equal to China and an earnings of about$30 billion from Foreign Direct Investment provide a solid base much incontrast to Pakistan’s import and aid driven economy.

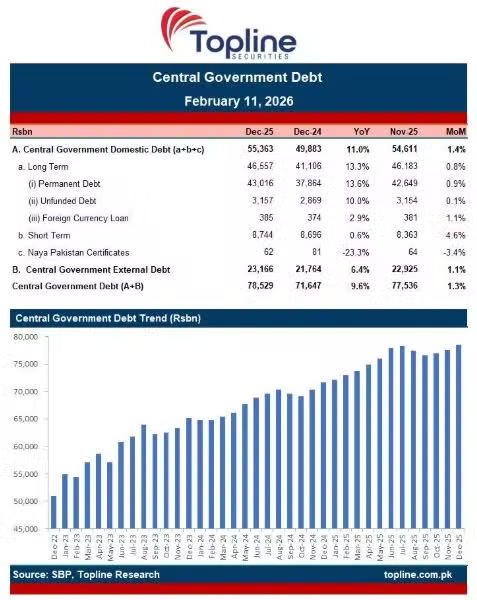

Pakistan, on the other hand, had to largely compromise on its nationalinterests by looking for bailout packages from the International MonetaryFunds and International donors with its political status already weak asthe mutual mistrust between the US and Pakistan had reached to new heights.To find a space in such an international politico-economic rivalry was anuphill task for Pakistan.

Hence, Senior US diplomat Alice Wells’ renewed criticism on theChina-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), during her visit in January, 2020,is a realistic tilt towards India. Evidently, the US allying itself withIndia more than Pakistan is more useful for the US and should beunderstandable. Her vehement criticism on the flagship projects of China’sBelt and Road Initiative (BRI) in repetition of her earlier remarks at theWilson Centre in Washington on Nov 21, 2019, represents simply politics ofpragmatism and interest. Similarly, the alleging lack of transparency inCPEC projects and the claims that Pakistan’s debt burden was growing due tothe Chinese financing is an argument in the same vein. Amb. Wells went evenfurther to declare that the companies blacklisted by the World Bank gotcontracts in the CPEC and had opposed the debt sequence as well. She alsosuggested that by getting Chinese financing for the projects, Pakistan wasbuying expensive loans which would eventually take a heavy toll on itsalready struggling economy.

Pakistan’s Foreign Minister, Shah Mahmood Quraishi’s talk about humanrights abuses by the Indian troops in the occupied Kashmir and intensifiedLoC ceasefire violations, assurances of Pakistan’s resolve for peace andstability in Afghanistan, was more of a diplomatic struggle to gain astrategic and political space in already strained relations and amidst agrowing Indo-US nexus. The US already considers India a ‘major defencepartner’ to facilitate defence technology, combat exercises and wargames.Joint projects have already been designed to include aircraft carriertechnologies and jet engines, futuristic helicopters, infantry combatvehicles, F-16/ F-18 fighter production line and billions of dollars’ worthof arms deals including the C-17 Globemaster, Poseidon-8, C-130 SuperHercules, Apache attack helicopters and Chinook heavy lift helicopters.Pakistan, on the other hand, has been denied for creating a strategicimbalance in the nuclear South Asian region ever since the Obama presidency.

The times of Donald Trump are no different with his new syndrome of*Islamophobia*. Though, Trump praised Pakistan’s role in War on Terror andin Afghanistan during his several rounds of meetings with Prime MinisterImran Khan, his earlier declaration of Pakistan as the most dangerouscountry after Iran and the relations promoted between India and the US byfour successive presidents prove enough evidence on the convergence oftheir interests. Pakistan has almost lost grounds to India. India holds asignificant place in the American strategy to contain China also. Theirpolicy of strengthening India’s conventional forces is growing with everypassing regime. The statement of Alice Wells should therefore be seen inthe light of the Mike Pompeo’s (the US Secretary of State) earlier warningto the International Monetary Fund (IMF). He said that the Trumpadministration will not allow it to lend US dollars to Pakistan forrepaying China. The looming threat of placing Pakistan on the FATFblacklist should also be taken as yet another arm twister with the same aim.

Based on this insensitivity, arrantly ignoring Pakistan’s legitimatesecurity and economic concerns is certainly a blow for a country which hadsuffered immense material damages amounting to over $120 billion during theUS War on Terror as a frontline ally. Hence, as is, can Pakistan rely onsuch passive diplomacy?

Understandably, the onus of understanding this dilemma in their relationslies more on the US. It can be safely held responsible for changing thebalance of power in South Asia with its consolidated political, strategic,monetary and military union with India. Its apathy towards the strategicbalance in the region with three nuclear powers; China, India and Pakistan,along with the Afghan quagmire cannot be ignored. Neither does it absolvePakistan for keeping all its eggs in one basket. Notwithstanding the fact,Pakistan remains a state of crucial relevance to the region. To revitalizeits role, Pakistan needs to look beyond the $5.5% projected GDP for 2020sas a catalyst towards regionalism of South Asia and bring its house inorder. Remarks of Daniel S. Markey of the Council on Foreign Relations(CFR), that, it “is anything but clear. A clean break between Pakistan andthe US seems unlikely, despite simmering disagreements over a number ofissues” cannot be ignored either. – Eurasia Review

**Shamsa Nawaz, Editor at Strategic Vision Institute, Islamabad*