ISLAMABAD – The world spinning with rapid change and throwing up newerchallenges every so often, it is deceptively easy to waltz into a ring offire for a short term gain than sustain the hard yards of a policy with noimmediate rewards.

Consider the recent maelstrom that resulted from livewire tensions betweenthe United States and Iran, which pitchforked countries on either side ofthe divide, with their respective alliances, with nary a palatable choice.Pakistan was no different in being put to the test, Gulf Times has reported.

However, in contrast to many other countries, which had little choice butto follow a narrower script in self-interest, Pakistan rose above thoseconsiderations and indulgently, pitched its tent for peace on all sides byproactively reaching out to them to save the day. Foreign Minister ShahMehmood Qureshi scurried to Iran, Saudi Arabia and the US in a matter of aweek to offer Islamabad’s unstinted support to nix the war drums.

What enabled Qureshi to carry the message with resonance lies in Pakistan’sstanding as perhaps, the only Muslim country in the world which can talk toanother Muslim country with a meaningful ability to play the peacemaker.

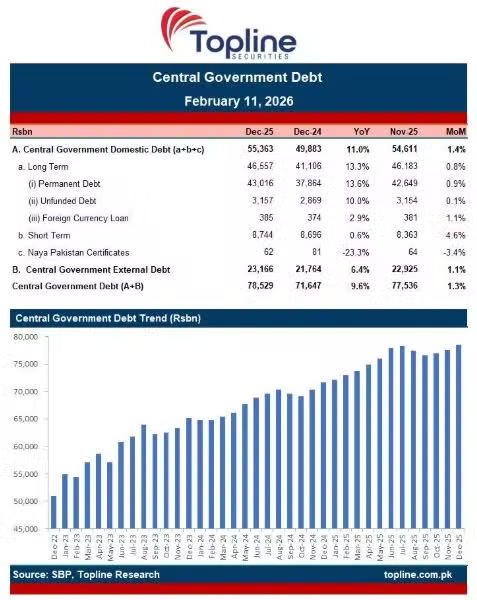

Nevertheless, it has been far from an easy ride for Islamabad given themultifarious economic issues it is currently seized with which have adirect bearing on both domestic stability and foreign policy.

Indeed, one of the outstanding challenges the Imran Khan-led government inIslamabad has faced since it came into power late summer in 2018 has beento strike a balance at virtually every turn. It is still an ongoing work —to set the house in order and pull back from the detrimental past policiesof pretty much keeping all the eggs in one basket, so-to-speak.

The foreign commentariat often betrays complacency in merely seeing it allfrom the prism of a relationship with one particular state or two, or therush to judgement as evident in the recent episode where Islamabadreluctantly pulled out of a summit in Kuala Lumpur. The optics may not havebeen ideal but the fact is that such decisions were — and are — driven bythe country’s core national interests, and the long-term future of Islamicunity.

It is a measure of considerable satisfaction for Pakistan that both Turkeyand Malaysia accepted the unity of purpose behind the decision and PrimeMinister Imran Khan continues to enjoy close ties with leaders of both thecountries with whom he had a frank discussion over the pullout. In fact,Khan is scheduled to visit Malaysia next month —for a second time only 17months into power — to reinforce ties that also have a personal imprint ofa close bond between him and Prime Minister Mahathir bin Mohamad.

Meanwhile, Islamabad’s studied attempt to expand the horizons of itsforeign policy goals is a reflection of its understanding of engagement ina multipolar world. To his credit, the PM has admitted mistakes in the pastthat drove Pakistan to side with a superpower in the so-calledwar-on-terror with colossal damage to the country in terms of men andmaterial losses that no other country has endured in a post-9/11 world.

“Pakistan will not become a part of any war,” he said while inaugurating askills development programme in Islamabad earlier this month. “Nobodyemerges victorious from wars.

Even the winner is a loser. Pakistan had paid a high price in the past bybecoming a part in the war-on-terror,” he recalled, adding: “Now, Pakistanwill not fight wars, but will bring countries together.”

Underpinning this paradigm shift was an engaging interaction on DefiningNational Security at ThinkFest 2020 in Lahore recently, where Moeed Yousuf,Special Assistant to the Prime Minister on National Security Division andStrategic Policy Planning, disclosed that Pakistan would have a coherentnational security policy by year-end with an inclusive economic diplomacy,ensuring security in all respects.

Yousuf, who is known for his depth of field in IR and diplomacy, and hasserved as Director of South Asia programs at the US Institute of Peace,taught at Boston University’s Political Science Department, deliveredlectures at the US State Department’s Foreign Service Institute and Nato’sCentre of Excellence Defence against terrorism in Turkey as well as thePakistan Military Staff College, is author of a handful of significantlyresearched books, consultant, and now a regular presence by the side of thePM in his foreign forays, asserted that Islamabad will soon ply by a robustsecurity policy strategised to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

Said Yusuf: “We are developing a coherent National Security Policy, whichintegrates foreign policy, internal security, education, population, globalwarming, culture and tourism, with a sole aim to ensure the social andeconomic security of the common man. We are breaking away from thetraditional definition of single-track geo-economic policy and nowintegrating all sectors to work in tandem to achieve the goal of upliftingthe common man.”

The PM’s Special Assistant underlined that including education in theoverall national security policy did not mean deploying guards outsideschools. “It would mean securing society by educating people and givingthem jobs. The economic diplomacy is the basic element of the government’splanned inclusive foreign policy,” he pointed out.

Countering the argument about the apparent futility of talking peace,Yousuf said: “Pakistan knows mediation will not bear fruit in thissituation (resulting from US-Iran tensions), but it’s time to engage indiplomacy to prevent escalation,” he said, citing that the media hadincorrectly criticised it as a mediation effort. “We are not doing it foroptics, but in the national interest,” he emphasised.

“Had we been doing it for optics, we would not have engaged Taliban, as theinternational media was unkind to Pakistan for being allied with them(Taliban),” Yousuf recalled, adding that if Islamabad can use its avenuesto bring peace in the region, then optics didn’t matter.

“(The new security policy) is a paradigm shift. It’s not going to happenovernight, but finally, it will be out (by the end of 2020). For 70 years,we have been functioning under short-term strategies,” he observed.

The PM’s Special Assistant also had one last interesting, if philosophical,pitch to make about the job at hand. “Our job at the National SecurityDivision is not to tell what will happen tomorrow, but what will happen dayafter tomorrow.”BY: Kamran Rehman